The Rorschach Test, also called the inkblot test, is a projective psychological test. Patients are shown various abstract inkblot images, and their associations are recorded. Based on their responses, conclusions about the person’s personality can be drawn. It is also referred to as a “personality projection test.” Swiss psychiatrist and psychoanalyst Hermann Rorschach developed this test. It is also used to diagnose thought disorders.

Initially met with scepticism in professional circles, the Rorschach Test gained popularity after Rorschach’s death, especially from the 1940s onward. It spread globally, particularly in the United States, France, and Japan, where it was used in clinical practice, legal assessments, and hiring processes. One advantage of the test is its resistance to manipulation, unlike questionnaires where individuals might influence results to their advantage.

The Rorschach Test has gained worldwide significance and remains an essential tool in psychological diagnostics, particularly for creating personality profiles and distinguishing between mental health conditions. The “International Rorschach Society” continues to focus on applying and advancing the test.

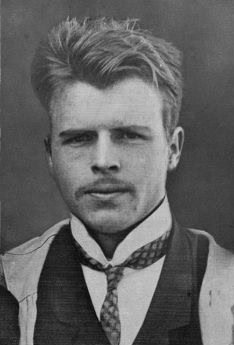

Herman Rorschah Biographical Note

Hermann Rorschach was born on November 8, 1884, in Zurich and grew up in Schaffhausen, where he attended the local canton school. Initially aspiring to become an artist, he ultimately decided to study medicine in Zurich to become a psychiatrist. During this time, he attended lectures by Eugen Bleuler and Carl Gustav Jung. Rorschach studied medicine in Zurich, Bern, and Berlin, completed his medical degree in 1909, and earned his state medical license in Zurich in 1912. He completed his doctorate under Eugen Bleuler with a dissertation titled On Reflex Hallucinations. Rorschach later developed the famous Rorschach inkblot test, also known as the inkblot test, which became a cornerstone in psychological evaluation. Today, the Rorschach assessment for personality remains a widely used tool for understanding thought patterns and diagnosing mental health conditions.

In 1910, he married his Russian colleague Olga Stempelin. The couple had two children. In 1913, they attempted to establish life in Russia, but this venture failed. Rorschach spent many years deeply involved in psychoanalysis and was appointed vice president of the Swiss Society for Psychoanalysis in 1919. His groundbreaking work, Psychodiagnostics, was published in 1921.

In December 1913, Rorschach travelled to Russia with his wife, intending to settle there. He worked at the private Krukowo clinic near Moscow before returning to Switzerland in the summer of 1914. He then served as an assistant physician at the Waldau psychiatric clinic near Bern. During this time, Rorschach’s scientific interests included studying rural religious sects in Bern, particularly the “Waldbruderschaft” (Forest Brotherhood) in the Schwarzenburg district and its founder, Johannes Binggeli. Although he planned a comprehensive study on Swiss sects, including their social history, Rorschach was unable to complete this work, though he published several related articles in professional journals.

In November 1915, Rorschach became the deputy director (“secondary physician”) at the psychiatric institution in Herisau, Appenzell. There, he developed the work that brought him lasting fame: Psychodiagnostics: Method and Results of a Perception Diagnostic Experiment (1921).

Rorschach died on April 2, 1922, in Herisau at the age of 37, following a fatal case of peritonitis caused by a delayed diagnosis of appendicitis.

Development of Rorschach Test

Hermann Rorschach was deeply interested in optical illusions. During his time in Russia, he collected composite images from newspapers, showing ambiguous forms like a “frog-cat” or “squirrel-rooster.” These ambiguous images fascinated him and influenced his work. Rorschach conducted 100 studies using inkblot images, which were carefully designed and always symmetrical. He tested his inkblots on hospitalised adolescents and individuals with schizophrenia, asking them what they saw in the images. He believed their responses could reveal insights into certain mental illnesses and personality traits.

After extensive revisions, Rorschach chose ten inkblots to present in a specific order. He asked participants the open question, “What might this be?” Rorschach’s images are not random smudges; they possess visual qualities beyond mere ambiguity. Each image holds an elusive aura of mystery that defies straightforward explanation.

Even today, a century later, the ten inkblots are still used. They challenge us to see them as a whole. While some describe the complete picture, others focus on the details. What do you focus on, and how easily can you shift between elements? Do you see movement and life in the images or only cold, lifeless forms?

One blot almost everyone identifies as a bat or moth—do you follow the obvious or insist on originality? Creating the cards required an artist, but analysing the results needed a scientist. Rorschach developed a system assigning codes and scores to responses. It categorised answers into “whole responses,” “detail responses,” and “movement responses.”

The test aims to identify patterns and proportions in descriptions, avoiding trivial associations. Seeing your mother in the ink doesn’t mean you’re obsessed with her. Rorschach initially didn’t call his method a “test.” He viewed it as an experiment in perception, exploring how people process visual information. Over time, he realised different personality types tend to perceive and describe the blots differently.

Rorschach knew the test would fall between disciplines: too emotional for scientists, too structured for psychoanalysts. In 1921, he wrote to a colleague that the work arose from two psychological approaches—analytical and empirical. Scientists found it too analytical, and analysts struggled with its structured, formal focus. For Rorschach, success lay in accurate, surprising diagnoses, which he believed would grow even more remarkable over time.

Rorschach Test–Procedure

The Rorschach Test takes approximately one hour to complete. Typically, the patient and examiner sit together at a table, with the examiner slightly behind to create a relaxed yet controlled atmosphere. The patient is presented with ten inkblot cards in a fixed sequence. The images include five black inkblots, two red, and three colourful ones. The cards are about 18×24 cm in size and symmetrical. Patients can rotate the cards freely and are asked, “What could this be?” They are encouraged to respond without censoring their thoughts. There are no right or wrong answers. The examiner notes reaction times, interpretations, and how the cards are handled. A second phase often follows, where the examiner asks questions about specific details of the responses.

The evaluation system of the Rorschach Test has changed significantly over time. This is largely due to criticism regarding the lack of objectivity in its analysis. Nevertheless, established algorithms or systems exist to categorise responses for meaningful conclusions.

Based on their descriptions of form, colour, and movement impressions, participants were categorised into psychological “experience types.” Drawing on Carl Gustav Jung’s typology, Rorschach identified three main types: “introversive,” “extratensive,” and “ambiequal” (a balance of the two). While Rorschach emphasised the relativity of psychological classifications and intended to refine and deepen his theoretical framework, he was unable to complete this work.

The standard evaluation typically examines five aspects:

- Localisation: Does the interpretation focus on the whole or details?

- Determinants: Are responses based on form, colour, or shading?

- Frequency of Responses: Are answers common or original compared to other test-takers?

- Content: What specific themes or ideas are present?

- Special Phenomena: Examples include rigidity, stupor, or delayed reaction times.

Despite modern advancements, many of Hermann Rorschach’s original principles remain valid. For example, he proposed that form-based responses reflect conscious functions and disciplined thinking. Colour-based answers indicate emotional resonance and affectivity triggered by the images. Movement responses provide insights into inner thought processes, such as introspection and creativity.

Based on these criteria, Rorschach identified four personality types linked to form, colour, and movement interpretations:

- Introversive: No focus on form or colour, but movement responses are strong.

- Extroversive: Emphasis on colour but no focus on form or movement.

- Constricted: No focus on form, with weak responses to colour and movement.

- Ambiequal: Strong responses to both colour and movement but not form.

In addition to personality typing, the test reveals other psychological traits. These include emotional, social, and intellectual characteristics and potential mental disturbances. However, interpretation often depends on the examiner’s psychodynamic knowledge and experience.

Rorschach Test: Global Use

After Hermann Rorschach’s death at only 37, the test’s development left his hands. Following the 1921 publication of his inkblot series, the test spread quickly, particularly in the USA. It became a cheaper, faster alternative to Freud’s dominant talk therapy. Known as the “X-ray of the unconscious,” it was applied far beyond its intended diagnostic purpose.

In the United States, it was used in the military and during Vietnam War investigations. It also played a role in interrogating Nazi prisoners during the Nuremberg trials in Germany. In Switzerland, Rorschach’s homeland, it was primarily used for job interviews and vocational tests. By the 1960s, its overuse in bizarre situations led to widespread criticism.

In some countries, like the UK, the test’s reputation never recovered from this backlash. However, in Japan, it has been a core psychological tool since 1925 and remains the most popular test. It also sees frequent use in Argentina and is gaining prominence in Turkey. In Russia, however, its significance has diminished. Despite this, the Rorschach Test has achieved global fame and recognition. If you’re seeking professional help to process these memories, connect with CHMC Clinic to start your journey toward healing.

Challenges in Using the Rorschach Test

The Rorschach Test has been extensively studied, with 118,000 publications listed on Google Scholar as of this article. It is still conducted today as it was 100 years ago. The test involves presenting the participant with ten standardised inkblot images and asking what they see. The examiner carefully records all responses. Interpretation considers not only what is seen—some common answers like spiders or butterflies are expected—but also how the participant analyses the images.

Does the participant focus on details or the entire inkblot? Do they notice colours or forms? Do they perceive movement or only static shapes? These observations aim to provide insights into the participant’s personality. However, how this is achieved remains debated. Hermann Rorschach did not provide detailed guidelines for interpreting his test, and two major approaches exist today.

In French-speaking countries, many practitioners align with the psychoanalytic tradition. While Rorschach himself was a psychoanalyst, he did not view his test as part of that method. The test’s flexibility in interpretation allows for subjective conclusions, which Nashat criticises as a risk of inconsistent results from identical responses.

Rorschach Test: Critical View

Since its publication in 1921, the Rorschach Test has faced criticism in psychiatry and psychology. The most common critique targets the subjectivity involved in evaluating and categorising responses. The wide range of possible combinations often leads to varying interpretations of test factors. Additionally, responses are frequently influenced by recent experiences rather than stable personality traits. Large studies also revealed that geographic and cultural differences significantly affect inkblot interpretations.

Due to these challenges, the Society for Personality Assessment issued a statement about the test in 2005. This statement confirmed the Rorschach Test’s validity, comparing its reliability to other accepted personality assessments.

Is There a Nazi Psyche?

Douglas McGlashan Kelley studied the leading Nazis in captivity. In 1945, allies arrested top Nazi leaders and planned to hold them accountable for their crimes at the International Military Tribunal in Nuremberg. In the months leading up to the trial, which began on November 20, 1945, they interned 22 prominent Nazis, first in Bad Mondorf (Luxembourg) and later in Nuremberg.

Fearing that the accused war criminals might commit suicide or be rescued by former comrades, the Allies implemented strict security measures in prison. Among the supervision team was Douglas McGlashan Kelley, an American doctor and psychiatrist. Kelley was tasked with both monitoring and interrogating the 22 Nazi leaders. From the outset, he was particularly interested in Hermann Göring, whom he weaned off his drug addiction, establishing a trusting relationship in the process.

An Investigative Aim

Kelley aimed to study the “character” of these 22 men during conversations, hoping to uncover the techniques they used to gain and maintain power. Over time, Kelley’s focus shifted. He wanted to determine whether the Nazis were “mentally ill,” suffered from “psychological disorders,” or if there was a distinct “Nazi psyche” or an inherent “tendency toward barbarism.” To test this theory, Kelley relied on limited methodological tools. One of these was the Rorschach test, a psychological diagnostic tool invented in 1921 by Hermann Rorschach. This test analyses personality traits based on participants’ associations with inkblot images.

Kelley’s intentions were genuinely investigative, not sensationalist. He believed that a thorough understanding of the “Nazi psyche” was essential to prevent a repetition of such atrocities.

A Painful Realization

However, as his investigations progressed, Kelley arrived at what he called the “painful realisation” that many people could potentially become war criminals and that absolute evil resides within everyone.

Kelley’s 1947 publication, 22 Cells in Nuremberg, earned him a university professorship and recognition as a criminology expert and police consultant.

Rorschach Test Summary

The Rorschach Test was developed in Zurich and named after its creator, Swiss psychiatrist and psychoanalyst Hermann Rorschach (1884–1922). He worked at the Burghölzli psychiatric university clinic in Zurich under Professor Eugen Bleuler, who introduced psychoanalysis to Switzerland and coined terms like “schizophrenia.”

In 1921, he published Psychodiagnostics, a book explaining his methods and findings. However, he had little time to expand his research, dying at 37 from untreated peritonitis. Connect with CHMC Dubai on Instagram for mental health insights

Hermann Rorschch Biographie in Bullet Points

- November 8, 1884: Born in Zurich.

- 1904–1909: Studied medicine in Zurich, Berlin, and Bern, attending lectures by Constantin von Monakow, Eugen Bleuler, and Carl Gustav Jung.

- 1909–1913: Assistant at the Thurgau psychiatric institution in Münsterlingen.

- 1910: Married Olga Stempelin.

- 1911: Conducted first experiments with inkblots.

- 1912: Earned a doctorate under Eugen Bleuler.

- 1914: Worked for six months as an assistant in a private psychiatric sanatorium near Moscow.

- 1915: Appointed secondary physician at the Cantonal Sanatorium in Herisau.

- 1917: Resumed inkblot experiments.

- 1921: Published the inkblot experiment series.

- April 2, 1922: Died suddenly in Herisau due to an undiagnosed appendicitis.